Assets

In early modern England, very elite or aristocratic figures (typically the eldest son) often inherited land or substantial estates. Such possession granted them longstanding (if gradually shifting) rights over the tenants and subjects “beneath them” and a measure of local religious and legal authority. A few individuals could reach, or at least come close to, such status thanks to newly acquired financial capital. But for those outside this small group of landowners, property (houses and possessions) could offer a different and relatively attainable way of marking themselves out as more prosperous than their neighbours. After all, status rested to a large extent on ownership of property, including buildings, household goods and clothing. However, what someone was “worth” also had a double meaning: the financial worth of their goods, but also having worth in terms of reputation (being considered ‘worthy’). These two ideas of worth were deeply connected.

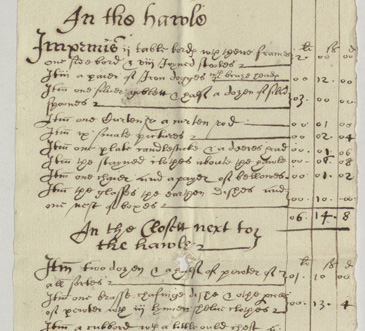

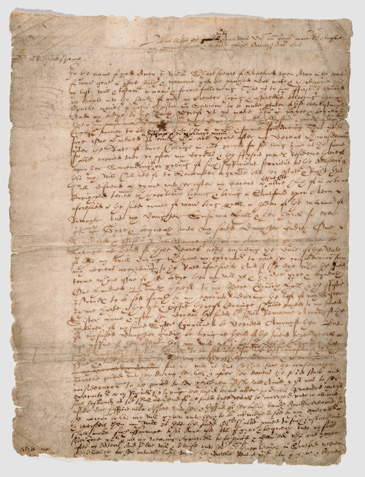

Expanding the quantity and quality of valuable possessions in turn enhanced reputation, and therefore status, within middling groups. Assets improved living standards but could also be sold in order to meet debts. Ownership of goods therefore suggested good creditworthiness, another important quality for members of the middling who operated in networks of business, trade and trust. Early modern society read value through the nature of materials and quality of craftsmanship. The scholar Alexandra Shepard has termed this a “culture of appraisal,” and it happened informally on a daily basis. People would regularly measure their worth against others’. Being able to judge the value of assets was also a key part of legal proceedings (which were very widespread in this period)— whether as a way of articulating self-identity in court testimonies or in taking an inventory of a neighbour’s goods following their death for the purposes of probate.

Assets - Showing 8 out of 66 exhibition objects